Egypt

Sisification of the Media – a Hostile Takeover

A hostile takeover of Egypt’s media is under way, leaving the influence on public opinion to be controlled by the state, the secret services and a few wealthy owners loyal to the regime and with close ties to the former president Hosni Mubarak.

In a move to gain influence over the State-owned media, the media giant Egyptian Media group signed several deals with the National Media authority on 20 January 2019 extending its control and increasing the influence of the General Intelligence over the Egyptian media landscape.

The coordinated attack on media freedom and pluralism is facilitated by a set of new laws restructuring the media sector in 2018 and by the ongoing pressure on journalists and media workers by the state.

“President al-Sisi has clearly been tightening his grip over the Egyptian media landscape in recent months” observed Olaf Steenfadt, project director of MOM. “The state is now the biggest owner in the broadcast field and orchestrates hostile takeovers to acquire full control over the whole media landscape”.

Concentrated markets in the hands of the State and the Intelligence Services

The MOM study analyzed 41 national Egyptian media outlets known to be the most popular ones in the country. It illustrates that, across all sectors, almost half of the media landscape is now concentrated in the hands of the state (through the National Media Authority and the National Press Authority, 36.6% of the surveyed media), and of intelligence bodies (through the Egyptian Media Group, 12.2%, and the Falcon Group, 4.9% of the surveyed media).

The print sector is concentrated around the public and state-owned Al Ahram Establishment, Dar Akhbar Al Youm and Dar El tahrir for Printing and Publishing as well as the private Al Masry Establishment for Press, Printing and Publishing and Advertising owned by prominent businessman Salah Diab.

The Egyptian Media Group, indirectly controlled by the secret service, dominates the broadcast sector, especially in satellite TV, closely followed by the state and by the privately owned Trenta and Cleopatra Media companies. The radio sector is largely dominated by the state as well, who owns radio stations directly or through the publicly-owned Nile Radio Company, followed by the privately-owned Nile Radio Productions and D Media for Media Production Company, which is also a key player in the TV sector.

By comparison, the online news and information market seems more diverse although the most popular platforms are digital versions of existing media outlets reinforcing their influence. Some of the most popular sites include Youm7 owned by The Egyptian Media Group, Masrawy owned by giant telecommunication tycoon Naguib Sawiris, Al Bawaba News owned by the Arab Center for Journalism led by MP Abdel Rahim Ali, and Sada El Balad News owned by Cleopatra Media Company.

With the state being owner and regulator at the same time, media companies operate in a heavily politicized field and with the secret services capturing ground, media pluralism is at the greatest risk ever in Egypt.

“Sisification” of the media system

Egypt’s strongman, Field Marshal Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, engineered a second term as president in early 2018. One of his first moves was to adopt a set of laws to reshuffle the media landscape and extend his powers on it, both in the public and the private sectors.

While the post-revolutionary constitution of 2014 required independent bodies to regulate the media sector, new laws authorize the president to directly appoint the head and some of the members of the newly created Supreme Council for Media Regulation, which holds the power to fine or suspend publications and broadcasters and issue or revoke licences (Law 180/2018). He also has the authority to appoint the head and some of the members of the National Media Authority (Law 178/2018) that governs the state-owned broadcast sector and the National Press Authority (Law 179/2018) for the state-owned print and online outlets. These two bodies are in charge of appointing and supervising board members and the executive management.

Since President al-Sisi took office, a dozen of once important media owners have seen their influence shrink, as they have been pushed to sell their shares partly or entirely to companies linked to intelligence bodies. Some managed to maintain some of their fading presence through the shareholding structure, and some others keep merely symbolic roles within the management of their own media outlets. Meanwhile, businessmen who support the current regime did not have to sell shares, for example Mohammed Abu El-Enein, the owner of Sada Al Balad, known to fully support al-Sisi's policies.

The president also appoints the head of the General Intelligence, which controls Egyptian Media Group (EMG), one of the most dominant media companies, through its own investment firm, Eagle Capital. Since 2016, EMG has been conducting a vast campaign to acquire shares in each media sector concluding a dozen deals to extend its control and reinforcing the leverage of the security apparatus in the sector. President al-Sisi also appoints the head of the Military Intelligence, which controls Falcon Group, a security company that also conducted deals in the media sector and acquired at least two TV networks and two radio stations since 2013.

As a result, the Egyptian intelligence services are now linked to twelve of the surveyed media entities: eight broadcast media outlets (Mega FM, Nagham FM and Shabee FM, Al Hayah, ON E, Extra News, DRN and El Radio 9090FM), two print outlets and their online editions (Al Youm Al Sabea, Al Watan).

Data in the mist

The Egyptian media market appears purposely opaque as the access to any piece of data is, though legally provided, effectively and actively blocked in practice.

Although transparency is officially required for any Egyptian media outlet registered as a company, the MOM team could not retrieve a single file from the Company Registry because an absurdly high fee was demanded illegally to access corporate information. As such, this type of data had to be considered as unavailable.

In addition – and, again, in theory – a new set of laws also requires each media outlet to publish financial statements and balance sheets, but the executive authority has not yet issued any of the executive sub-regulations to allow these laws to be enforced. As a result, financial information and management data was unavailable to the MOM team.

Particularly, the heavy investments in the media sector made by the General Intelligence raise questions. Some investigation points towards the United Arab Emirates as a source, but this could not be confirmed independently and, not surprisingly, the secret service remains rather secretive in this regard.

Last not least, audience data is being monopolized by the Egyptian State and kept secret, too. Even though the MOM researchers managed to gather, validate and analyze a vast set of information with the help of reliable sources such as local experts, we are not allowed to release the actual numbers until further notice. The Supreme Council for Media Regulation urges market research firms not to publish the results of any surveys until they are endorsed by the Council – which usually never happens. So to this day, no single survey on media consumption in Egypt is publicly available.

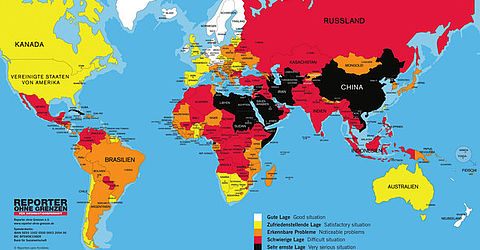

Physical and legal abyss

Arbitrary interrogations and detentions, violence against journalists by the state and impunity for related crimes create an extremely insecure and dangerous environment to work in. As a result, Egypt is the first out of 21 MOM country editions published or in the making where Reporters without Borders’ staff didn’t dare to enter the country and where our local partner organisation is not being mentioned due to security concerns. All websites of RSF including MOM are among the many hundreds that are blocked inside Egypt. We therefore decided to host it on a Tor server as well in order to allow for access from within the country.